Chile’s president receives draft of new constitution

Chile’s new draft constitution has been submitted to President Gabriel Boric, after a year-long process that saw constituent assembly members debate and write up a document to replace the country’s Pinochet-era magna carta.

The new text, which will replace the constitution written during the 1973-1990 dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet, aims to establish new social rights.

It was drawn up by the Constitutional Convention – a constituent assembly of 154 citizens, most of whom were political independents, that will be dissolved a year to the day after it began work on July 4, 2021.

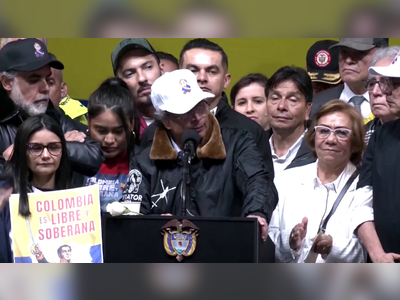

“We should feel proud that during the deepest crisis … in decades that our country has lived through, we Chileans have chosen more democracy, not less,” Boric, a left-wing former protest leader who was sworn into office in March, said during a ceremony in the capital, Santiago.

He immediately signed a decree calling a referendum on September 4, where voting in the deeply polarised country of 19 million people will be obligatory.

“This September 4, it will once again be the people who will have the last word on their destiny,” Boric also said in a tweet. “Today begins a new stage where everyone makes history.”

In the first of the new constitution’s 388 articles, Chile is described as “a social and democratic state of law”, as well as “plurinational, intercultural and ecological”.

Chile “recognises the dignity, freedom, substantial equality of human beings and their indissoluble relationship with nature as intrinsic and inalienable values”, says the new constitution.

Chileans voted last year for the Constitutional Convention members who would work to replace the Pinochet-era constitution, which critics blamed for long-standing socioeconomic inequalities in the South American nation.

Calls for a new constitution grew out of mass 2019 protests that broke out in anger over rising costs of living and other issues.

Fed up with the political status quo and urging systemic reforms, Chilean voters elected dozens of progressive, independent delegates to redraft the new constitution – dealing a surprise blow to conservative candidates who failed to secure a third of the seats to veto any proposals.

Split equally between men and women, the Constitutional Convention also contained 17 seats reserved for Indigenous people, who make up around 13 percent of Chile’s population.

As well as recognising the different peoples that make up the Chilean nation, the new constitution accords a certain amount of autonomy to Indigenous institutions, notably in matters of justice.

“We’re very excited about it,” Gaspar Dominguez, vice president of the constituent assembly, told Al Jazeera after the draft was finalised.

Al Jazeera’s Lucia Newman, reporting from Santiago on Monday, said the new constitution “dramatically change[s] the status quo” in Chile.

“It’s a feminist constitution that guarantees gender parity all through the state system, including in the next Congress. It also describes Chile as a pluri-national country; it’s only the third country in the world that would have that definition,” she said.

“For the Indigenous people of this country, it would give them more land, more say, more autonomy – that is very controversial. It is also the world’s first – you could call it – ‘environmental constitution’ that specifically protects the environment.”

Several times in recent weeks, Boric has reiterated his support for the constitutional project, adding that the current document represents an “obstacle” to profound social reform.

Even so, several opinion polls suggest the new constitution may yet be rejected. With the full text still to be published, many Chileans say they are unsure.