Haiti receives its first batch of cholera vaccines to tackle deadly outbreak

Haiti has received its first shipment of cholera vaccines since an outbreak was declared more than two months ago.

The first of the 1.1m doses, delivered last week, will be distributed in the capital, Port-au-Prince, and surrounding areas in the hope of stemming the spread of the disease, which has been aided by political instability and lawlessness.

“The arrival of oral vaccines in Haiti is a step in the right direction,” said the director general of Haiti’s health ministry, Lauré Adrien.

The vaccine campaign is expected to begin in the coming days and will target children and adults over the age of one in Ouest, where Port-au-Prince is situated, and Mirebalais regions, where most cases have been reported.

According to the latest health ministry data, the Ouest region saw the highest number of suspected cases last week. The vaccines have come late and will be slow to deliver.

The supplies, sent from the International Coordinating Group on Vaccine Provision, a partner of the World Health Organization that manages global vaccine stockpiles, were held up by the brutal violence engulfing Haiti, which has prevented medical supplies from reaching the Caribbean country.

NGOs say it will be impossible to send vaccines to much of the countryside as gangs control the roads out of the capital. Vaccine hesitancy is also expected to be high.

Cholera is having a global resurgence, a result of numerous humanitarian crises and global heating. “The map is under threat (from cholera) everywhere,” said Dr. Philippe Barboza, of the World Health Organization, last week as the UN said there were cases of infection in around 30 countries, whereas in the previous five years, fewer than 20 countries reported infections.

Since an outbreak was declared in Haiti in October, 13,000 people have been hospitalised and more than 300 – many of them children – have died.

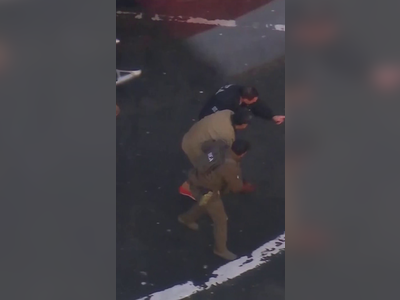

A man with cholera symptoms is helped at a

clinic in Port-au-Prince, October 2022. For the first time in three

years, people in Haiti have been dying of cholera.

A man with cholera symptoms is helped at a

clinic in Port-au-Prince, October 2022. For the first time in three

years, people in Haiti have been dying of cholera.

The last cholera epidemic was in 2010 after the country was rocked by a 7.0 magnitude earthquake. In the ensuing eight years, 820,000 people were infected and 10,000 died.

Today, Haiti could provide even more fertile ground for the bacterial disease, which is spread through contaminated water and food.

The country has been plunged into chaos by warring gangs who are capitalising on a power vacuum left by the assassination of the country’s president in July 2021 to take control of the capital.

“It really is the perfect storm,” said Fiammetta Cappellini, the Haiti country representative for the Avsi Foundation, an Italian NGO.

Most cholera infections have been confined to Port-au-Prince, where violence has severely hampered response efforts. When the G9 gang took over the country’s principal fuel terminal on 4 October, fuel shortages knocked out water pumps and hospitals relying on generators for power.

Epidemiologists said the fuel scarcity halted mobility across the country, which slowed infections. But since the government retook the terminal in November, fuel is more readily available allowing the virulent disease to spread faster to the rest of the country.

This month, the UN said eight of the country’s 10 regions now have confirmed infections, which it described as a “worrying trend”.

“People in rural areas are using river water and spring water as there is no potable water, so when the water source is compromised the entire community is affected,” said Mario Di Francesco, a cholera expert at Avsi.

While in Port-au-Prince medical teams are able to negotiate with rival factions to enter neighbourhoods and distribute water and chlorinate water supplies, few NGOs can reach the country’s more remote corners, which are cut off by roadblocks.

An unprecedented hunger crisis has made diarrhoea and dehydration, two symptoms of cholera, particularly deadly, and experts fear that regions outside the capital could be particularly vulnerable.

The violence has forced many international organisations to abandon the country, leaving those who remain overstretched.

“When cholera hit after the earthquake we had a lot of international help and support from humanitarian agencies. Now there are very few of us,” said Cappellini. “Working, and just living here, is a nightmare.”

A baby sick with cholera receives treatment at a clinic run by Médecins Sans Frontières in Port-au-Prince in November.

A baby sick with cholera receives treatment at a clinic run by Médecins Sans Frontières in Port-au-Prince in November.

Haiti’s rural hospitals are also fragile. Many facilities were forced to shut in October due to fuel shortages and at least three babies have died in hospitals in the capital due to national oxygen shortages, said Magda Cheron, from the non-profit FHI 360, who directs a USAid-funded programme to supply oxygen to public hospitals. One of the hospitals on the outskirts of the city couldn’t get oxygen because gangs blocked the road.

The latest concern is the dwindling supplies of IV fluids, which are key to rehydrating cholera sufferers.

The Sacre Coeur hospital, a private facility in Milot, northern Haiti, has managed to stay one step ahead of the disease, said its director, Harold Prévil. The slow spread across the country bought them enough time to replenish basic medical supplies from the neighbouring Dominican Republic.

“Maybe God is on our side, because we are lacking the essentials to handle a big surge,” said Prévil.

But public hospitals are not so well equipped and staff fear that fragile facilities could collapse if they are hit by a sudden increase in cases.

There is little hope supplies would be restocked quickly, said Blaise Hamidou, a water and sanitation manager at Mercy Corps.

“We have had supplies in Port-au-Prince before early September but we cannot shift those supplies to the south of Haiti, even after the reopening of the petrol port last month,” Hamidou said.

Airlink, an American non-profit that delivers medical supplies, has 56 tonnes of aid in European warehouses. It has been unable to ship them because of a lack of air cargo space, and because it’s too unsafe to be collected on the other side.

The end of the rainy season – and therefore less flooding – offers some hope in reducing infections. But the Christmas holidays and February’s carnival could lead to another rise. Rumours are also circulating that fuel prices will rise, which could bring more protests.

“It’s just one crisis to the next,” said Cappellini. “The country is dying, and we’ve no reason to think it will get better tomorrow.”