Hungary: Criticism makes it hard to cooperate with West

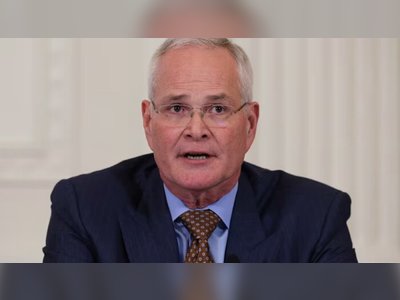

The West’s steady criticism of Hungary on democratic and cultural issues makes the small European country’s right-wing government reluctant to offer support on practical matters, specifically NATO’s buildup against Russia, Hungary’s foreign minister said.

In an interview with AP, Hungarian Foreign Minister Péter Szijjártó also said Friday that his country has not voted on whether to allow Finland and Sweden to join NATO because Hungarian lawmakers are sick of those countries’ critiques of Hungarian domestic affairs.

Lawmakers from the governing party plan to vote Monday in favor of the Finnish request but “serious concerns were raised” about Finland and Sweden in recent months “mostly because of the very disrespectful behavior of the political elites of both countries toward Hungary,” Szijjártó said.

“You know, when Finnish and Swedish politicians question the democratic nature of our political system, that’s really unacceptable,” he said.

A vote on Sweden is harder to predict, Szijjártó said.

The EU, which includes 21 NATO countries, has frozen billions in funds to Budapest and accused populist Prime Minister Viktor Orban of cracking down on media freedom and other rights. Orban’s administration has also been accused of tolerating an entrenched culture of corruption and co-opting state institutions to serve the governing Fidesz party.

In a European Parliament resolution, EU lawmakers declared last year that Hungary had become “a hybrid regime of electoral autocracy” under Orban’s nationalist government and that its undermining of the bloc’s democratic values had taken Hungary out of the community of democracies.

That criticism raised objections within Hungary and made it hard for the government to support Finland and Sweden’s bids to join NATO, Szijjártó said. Skeptics insist that Hungary has simply been trying to win lucrative concessions.

When it comes to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Szijjártó said that his country’s advocacy of peace does not mean accepting that Russia would keep the territory it currently controls.

“You know, stopping the war and sitting around the table does not mean that you accept the status quo,” he said. “When the war stops and the peace talks start, it’s not necessary that the borders would be where the front lines are. We know this from our own history as well ... Cease-fire has to come now.”

As for relations with the United States, Szijjártó said they had a heyday under former President Donald Trump. His government found things more difficult under President Joe Biden.

In perfect, nearly unaccented English, Szijjártó explained that Hungary is “a clearly rightist, right-wing, Christian Democratic, conservative, patriotic government.” He then went on in terms that would be familiar to millions of Americans.

“So we are basically against the mainstream in any attributes of ours. And if you are against the liberal mainstream, and in the meantime, you are successful, and in the meantime, you continue to win elections, it’s not digestible for the liberal mainstream itself,” he said. “Under President Trump, the political relationship was as good as never before.”

Key to that relationship was Trump’s acceptance of Hungary’s policies toward its own citizens.

The law has been condemned by human rights groups and politicians from around Europe as an attack on Hungary’s pride community.

Szijjártó said Trump was more welcoming of such measures than the Biden administration.

“He never wanted to impose anything. He never wanted to put pressure on us to change our way of thinking about family. He never wanted us to change our way of thinking about migration. He never wanted us to change our way of thinking about social issues,” Szijjártó said.

He also said Trump’s attitude toward Russia would be more welcome by some parties today.

During Trump’s term in the White House, Russia did not start “any attack against anyone,” Szijjártó said.

Lawmakers from the governing party plan to vote Monday in favor of the Finnish request but “serious concerns were raised” about Finland and Sweden in recent months “mostly because of the very disrespectful behavior of the political elites of both countries toward Hungary,” Szijjártó said.

“You know, when Finnish and Swedish politicians question the democratic nature of our political system, that’s really unacceptable,” he said.

A vote on Sweden is harder to predict, Szijjártó said.

The EU, which includes 21 NATO countries, has frozen billions in funds to Budapest and accused populist Prime Minister Viktor Orban of cracking down on media freedom and other rights. Orban’s administration has also been accused of tolerating an entrenched culture of corruption and co-opting state institutions to serve the governing Fidesz party.

In a European Parliament resolution, EU lawmakers declared last year that Hungary had become “a hybrid regime of electoral autocracy” under Orban’s nationalist government and that its undermining of the bloc’s democratic values had taken Hungary out of the community of democracies.

That criticism raised objections within Hungary and made it hard for the government to support Finland and Sweden’s bids to join NATO, Szijjártó said. Skeptics insist that Hungary has simply been trying to win lucrative concessions.

When it comes to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Szijjártó said that his country’s advocacy of peace does not mean accepting that Russia would keep the territory it currently controls.

“You know, stopping the war and sitting around the table does not mean that you accept the status quo,” he said. “When the war stops and the peace talks start, it’s not necessary that the borders would be where the front lines are. We know this from our own history as well ... Cease-fire has to come now.”

As for relations with the United States, Szijjártó said they had a heyday under former President Donald Trump. His government found things more difficult under President Joe Biden.

In perfect, nearly unaccented English, Szijjártó explained that Hungary is “a clearly rightist, right-wing, Christian Democratic, conservative, patriotic government.” He then went on in terms that would be familiar to millions of Americans.

“So we are basically against the mainstream in any attributes of ours. And if you are against the liberal mainstream, and in the meantime, you are successful, and in the meantime, you continue to win elections, it’s not digestible for the liberal mainstream itself,” he said. “Under President Trump, the political relationship was as good as never before.”

Key to that relationship was Trump’s acceptance of Hungary’s policies toward its own citizens.

The law has been condemned by human rights groups and politicians from around Europe as an attack on Hungary’s pride community.

Szijjártó said Trump was more welcoming of such measures than the Biden administration.

“He never wanted to impose anything. He never wanted to put pressure on us to change our way of thinking about family. He never wanted us to change our way of thinking about migration. He never wanted us to change our way of thinking about social issues,” Szijjártó said.

He also said Trump’s attitude toward Russia would be more welcome by some parties today.

During Trump’s term in the White House, Russia did not start “any attack against anyone,” Szijjártó said.

Comments

Oh ya 3 year ago

Yes a country that sees that supporting the NAZIS in Ukraine is wrong. More people are waking up to the fact that Russia is just doing what the world was doing in WWII. Fighting NAZIS. And that is what Ukraine is today